Everyone says the secret to college success starts with going to class. But that’s where most people leave it. They don’t say what they mean by going to class. Here we’re going to explain what going to class means and situate it in a larger cycle that is the real secret to college success.

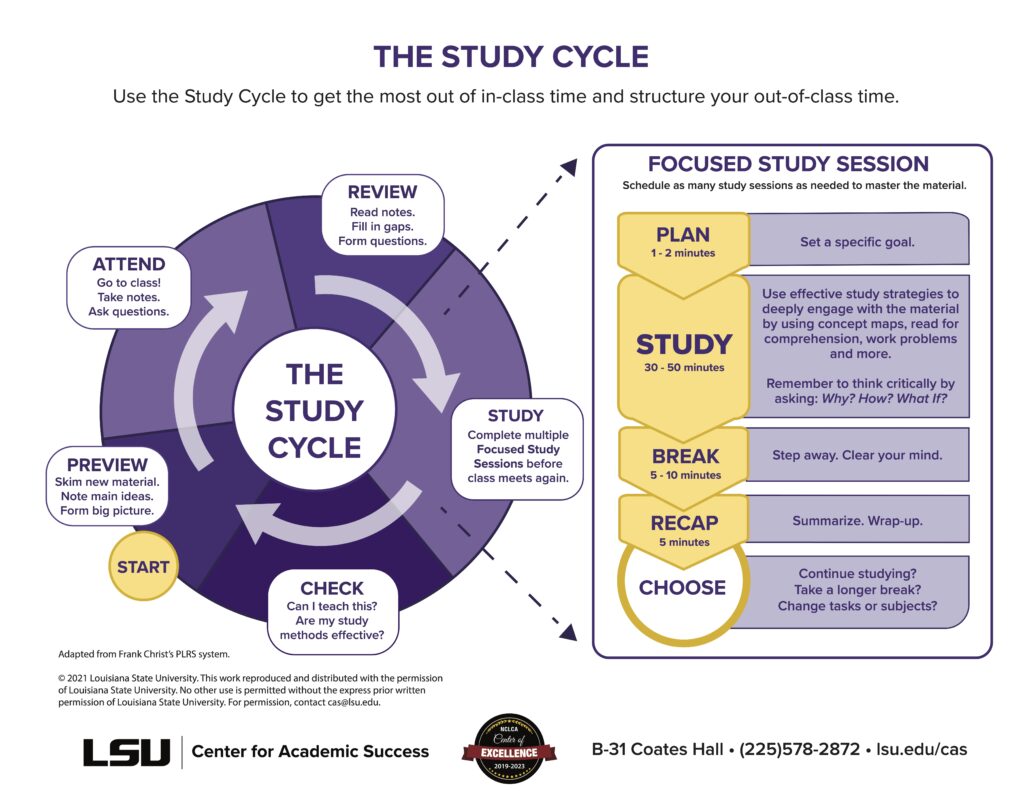

Going to class is just one step in a five-part cycle called the Study Cycle. Embedding focused study sessions in a cycle of previewing, attending, reviewing, and checking maximizes your learning. Using proven effective study strategies to engaging in effortful study ensures that your learning is lasting and retrievable when you need it.

What to do BEFORE class – Preview

When you preview, you’re trying to familiarize yourself with the material you’re going to learn. You’re working to see the big picture and identify the key concepts.

- Complete preparatory assignments such as

- assigned readings

- viewing recorded lectures

- previewing slides and other material available on the course management system (Brightspace at UNE, Canvas or Blackboard at other universities)

- Identify the learning outcomes or objectives for the upcoming lesson

- Set up note taking pages for lecture in advance – one page for each learning outcome identified

- Identify how the new material connects with previous material in the course and related courses and with your existing knowledge

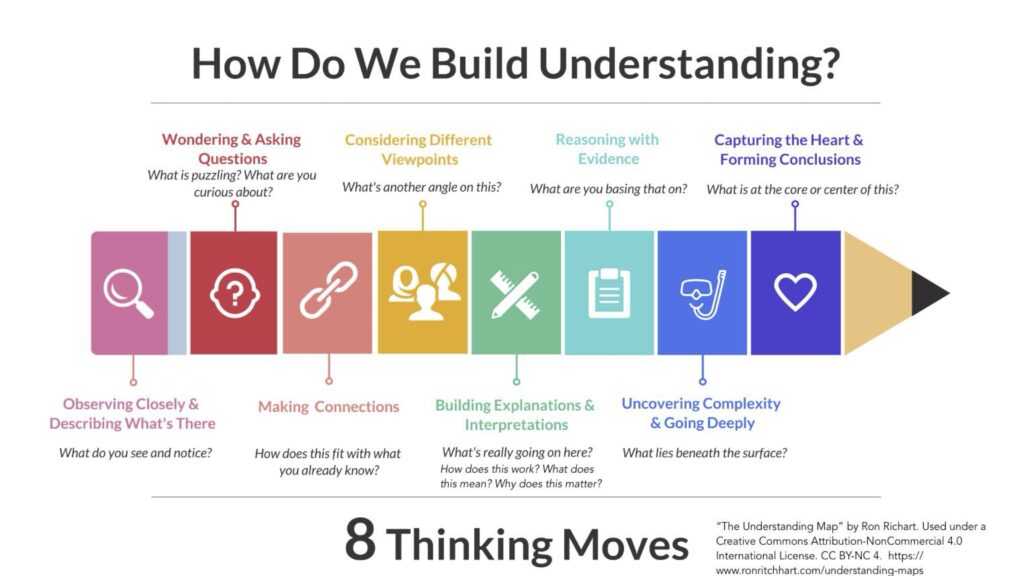

- Figure out your own motivation for learning the material – did you know that every undergraduate course helps you develop fluency with 8 core thinking moves?

What to do DURING class – Attend

Did you know that in addition to “show up,” “attend” also means “listen” or “pay attention”?

When you attend class, your goal should be to engage the material. Since you already have the big picture from your preview, pay attention to how the details fit together, what they mean, and how they can be used.

- Create a conducive learning environment

- close irrelevant tabs on your device

- put your phone somewhere where it won’t be easy to get to during class

- sit in a location in class where you won’t be distracted by other students

- Did you know that sitting near the front of the class correlates with higher grades?

- have necessary learning supplies ready to hand – notebook, writing tool, textbook, reading notes, completed preparatory assignments, fidget toys…

- Stay engaged by taking notes, writing down and asking questions, making connections, identifying confusing parts of the lesson, doing (not just watching) the problems being demonstrated in class, and participating fully in class and small group work

- Focus on concept clusters and the examples that make sense of them

- Connect discrete pieces of information to the learning objectives that pull them together

What NOT to do IMMEDIATELY AFTER class

The 15 minutes to half hour immediately after class are a crucial time for consolidating in memory what you’ve just learned in class. Your brain is already working at a high level of cognitive load, and it needs its remaining available resources to run the memory consolidation process that commits the material to long-term memory.

If you add to your brain’s cognitive load by listening to music or using your phone to view social media or do any other activity that requires attention and adds to the load, you are interfering with your ability to form the memories you’ll need to retrieve later when you want to use what you’ve learned (say on a test).

So after class, instead of listening to music, watching videos, or scrolling on your phone, relax, take a quiet walk, or find a sensory-reduced place to be for a little while to allow your brain time to start building the first physical connections between neurons it needs to form a memory. Then make sure you get a good night’s sleep.

Source for the idea that new, irrelevant inputs can interfere with memory consolidation: Sridhar, S., Khamaj, A., & Asthana, M. K. (2023). Cognitive neuroscience perspective on memory: Overview and summary. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 17, 1217093. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2023.1217093

Key quote: “Interference from new learning events or disruption caused due to inhibition can abort this cycle leading to incomplete consolidation (Josselyn et al., 2015).”

What to do AFTER class, Pt. 1 – Study/Encode/Retrieve

Unless you study – which means rehearsing and retrieving the material you’re learning – your new knowledge won’t make it into your long-term memory and be intergrated into your knowledge-base and be available for use. Cramming doesn’t lead to learning. Space out your rehearsal and retrieval practice over a period of weeks. Make sure you’re connecting what you’re learning this week to what you’ve learned earlier in the class and what you already knew before. Be sure to rehearse older material as well as the new material or it will fade.

- Study using effective learning strategies (see the poster below) that work on higher levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Learning. Move beyond remembering and understanding. Learn the material well enough to analyze, connect (synthesize), apply, evaluate, and create with it. Learn it well enough to teach it to someone.

- Here’s a list of individual and group study strategies keyed to the different levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy with variations tailored to STEM, the social sciences, and the humanities.

- Identify the concepts, skills, or processes that you want to learn in this session, the questions you want to answer, the problems you want to solve

- Determine various metrics for a “successful” session

- quantity: number of problems completed, concepts learned, paragraphs written,

- quality: Deeper focus, richer understanding, easier recall

- process: Used proven effective study strategies, consecutive minutes spent studying without distraction, was able to refocus quickly when interrupted

- Practice retrieving information and concepts without notes, spacing your practice out across several study sessions

- Develop fluency in skills by practicing intentionally

- break the skill down into its component elements

- target your practice at the specific parts that give you trouble

- practice should feel effortful; if it doesn’t, you’re probably practicing the wrong parts

- assess your practice continuously: notice when you make mistakes and do some block practice on the skill to improve your fluency

- get frequent expert feedback on your performance

- evaluate the quality of your skill. Practice until it’s very rare for you to get it wrong.

- Turn class notes into learning/study notes organized by learning objects in a way that connects concepts to one another

- Use tutoring – bring questions, explain things to the tutor and see if you’re right, get feedback on your understanding

- Use collaborative study techniques

What to do AFTER class, Pt. 2 – Check

- Take a practice test without using notes (use earlier edition textbooks found in your college library for material)

- Teach the material to someone else

- Draw diagrams and write formulas from memory

- Do a brain dump – write down everything you know without referring to notes or textbooks

What to do AFTER class, Pt. 3 – Reflect

- Write down the most important things you learned during your study session

- Write down what you still don’t quite understand or know how to do

- Identify the material you totally missed during your “checking” activities

- Identify the material you only partially remembered and understood while checking

- Identify the material you believe you have mastered

- Ask yourself open-ended questions below for self-assessment

- During this session, was I focused, productive,…. How do I know?

- Did my study session feel effortful?

- What level(s) of Bloom’s taxonomy did I work on?

- What proven-effective study practices did I use?

- How effective were the study strategies I used?

- Did I allocate an appropriate amount of time to learn the material?

- Next session, I want to improve ____ by ______.

- To have a better session next time, I need _____ [resources, preparation, …]

- Write down goals for next time and schedule your next study session

- Go back to “Study” mode

Click on the image below to learn more about the Six Strategies for Effective Learning